| A page for those special

studies of turkeys, and the dogs we hunt them with. |

(Continued from the

top of the History

page): The Role of Prehistoric Peoples in Shaping

Ecosystems in the Eastern United States: Implications

for Restoration Ecology and Wilderness Management by

Thomas W. Neumann 1491:

New

Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus (Continued from the

top of the History

page): The Role of Prehistoric Peoples in Shaping

Ecosystems in the Eastern United States: Implications

for Restoration Ecology and Wilderness Management by

Thomas W. Neumann 1491:

New

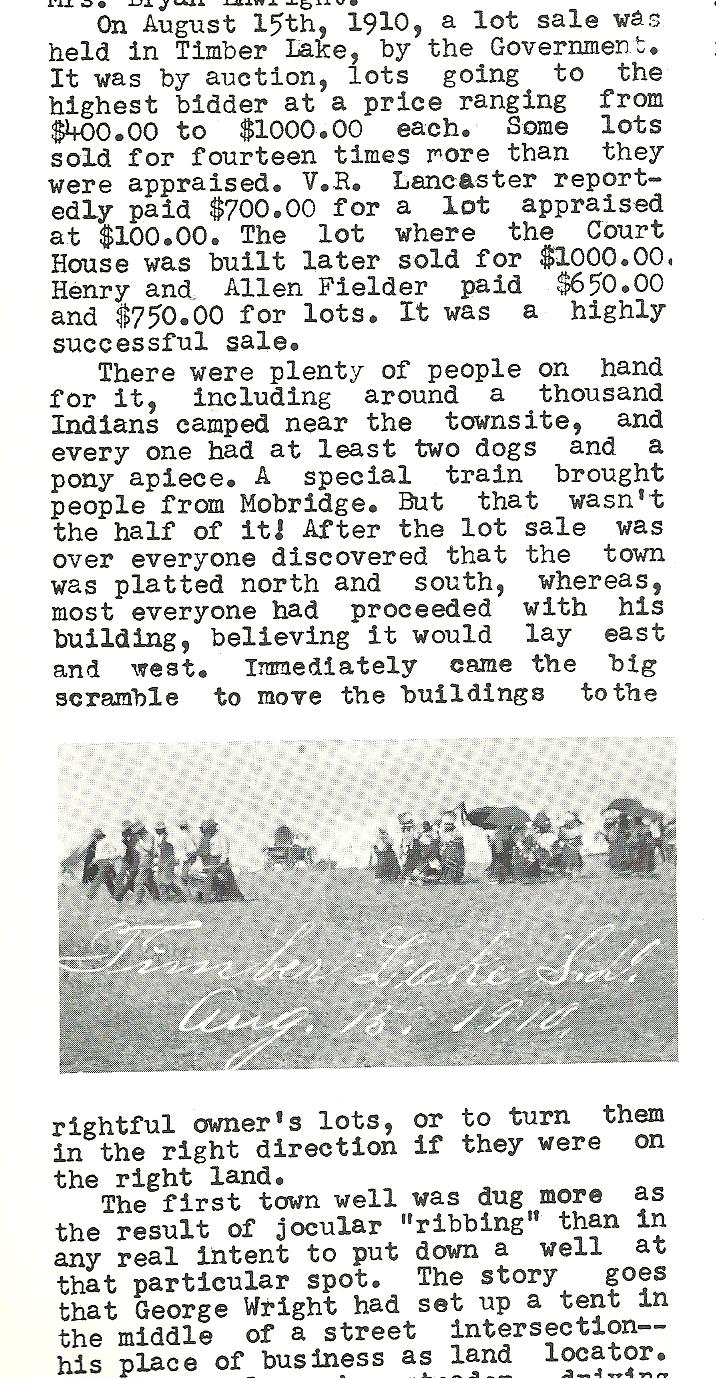

Revelations of the Americas Before ColumbusJust as the epidemic diseases introduced by the Europeans into the Americas (smallpox, viral pneumonia, hepatitis, influenza, measles, tuberculosis, meningitis, cholera, typhus, scarlet fever) eliminated most of the Indians, the canine diseases the native dogs had no immunity to, killed the majority of them. 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created The turkey hunting dog was an American original. The technique was taught by the Indians, but the breeds were European. History tells us the training, breeding and raising of turkey dogs began and still continues in those states that are part of the Appalachian mountains, but primarily Virginia and Pennsylvania. There, families of the most serious turkey hunters bred dogs with similar traits for generations (of men and dogs). We can't say for sure, who was the first person to hunt turkeys with the help of dogs, or how they did it. But we're reasonably sure we know where they began.  passed

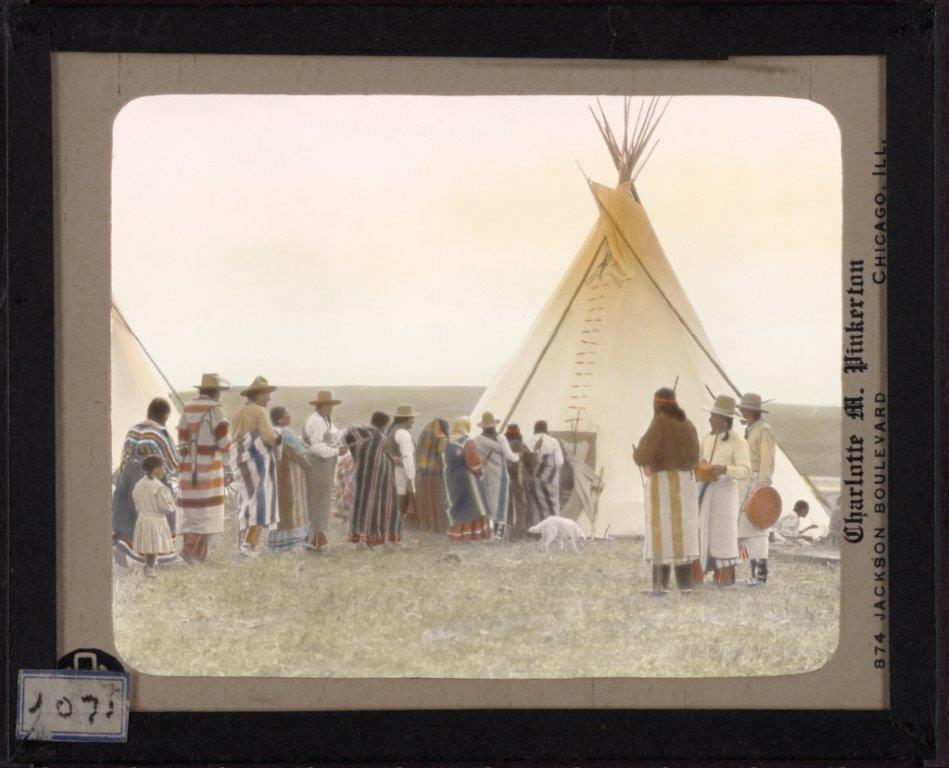

their techniques on to the white man (see 1854

illustration below by E.J. Lewis). Proof the Indians

loved their dogs: In 1910, the Sioux Indians in South

Dakota had at least two dogs apiece. Click

on picture to the right, from when the government sold the

land that was part of the Standing Rock and the Cheyenne

River Indian Reservations, this book said the Indians

had 2 dogs apiece. Schorger says in 1608, the Indians

around Jamestown, Virginia used their cur dogs to

hunt turkey and other game. See 1973 below (Even the

Indians owned turkey dogs). The technique was taught by

the Indians. passed

their techniques on to the white man (see 1854

illustration below by E.J. Lewis). Proof the Indians

loved their dogs: In 1910, the Sioux Indians in South

Dakota had at least two dogs apiece. Click

on picture to the right, from when the government sold the

land that was part of the Standing Rock and the Cheyenne

River Indian Reservations, this book said the Indians

had 2 dogs apiece. Schorger says in 1608, the Indians

around Jamestown, Virginia used their cur dogs to

hunt turkey and other game. See 1973 below (Even the

Indians owned turkey dogs). The technique was taught by

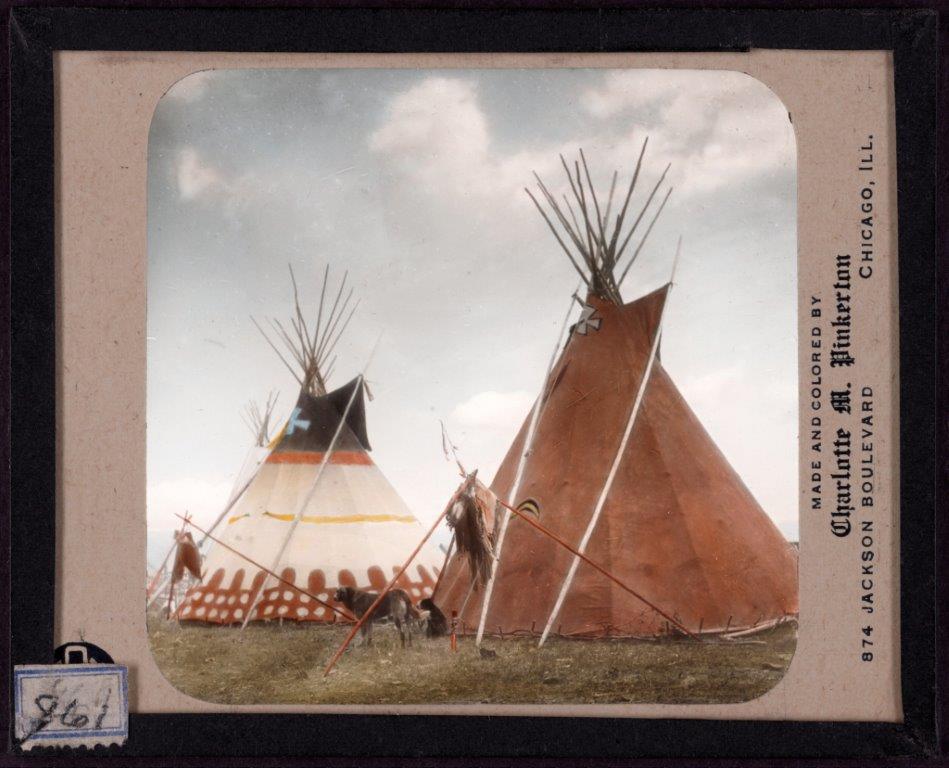

the Indians.Indian tipi dogs courtesy: Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library https://beinecke.library.yale.edu/   While our oldest stories

of spring turkey hunting in the United States come

from the early 1900's (Rutledge 1907, Jordan/McIlhenny

1914, Turpin 1924, Everitt 1928, Mosby and Handley 1943,

Davis 1949), the earliest references to fall

turkey dogs go back to the 1600's. Those below are

mentioned on this site, unless noted otherwise: While our oldest stories

of spring turkey hunting in the United States come

from the early 1900's (Rutledge 1907, Jordan/McIlhenny

1914, Turpin 1924, Everitt 1928, Mosby and Handley 1943,

Davis 1949), the earliest references to fall

turkey dogs go back to the 1600's. Those below are

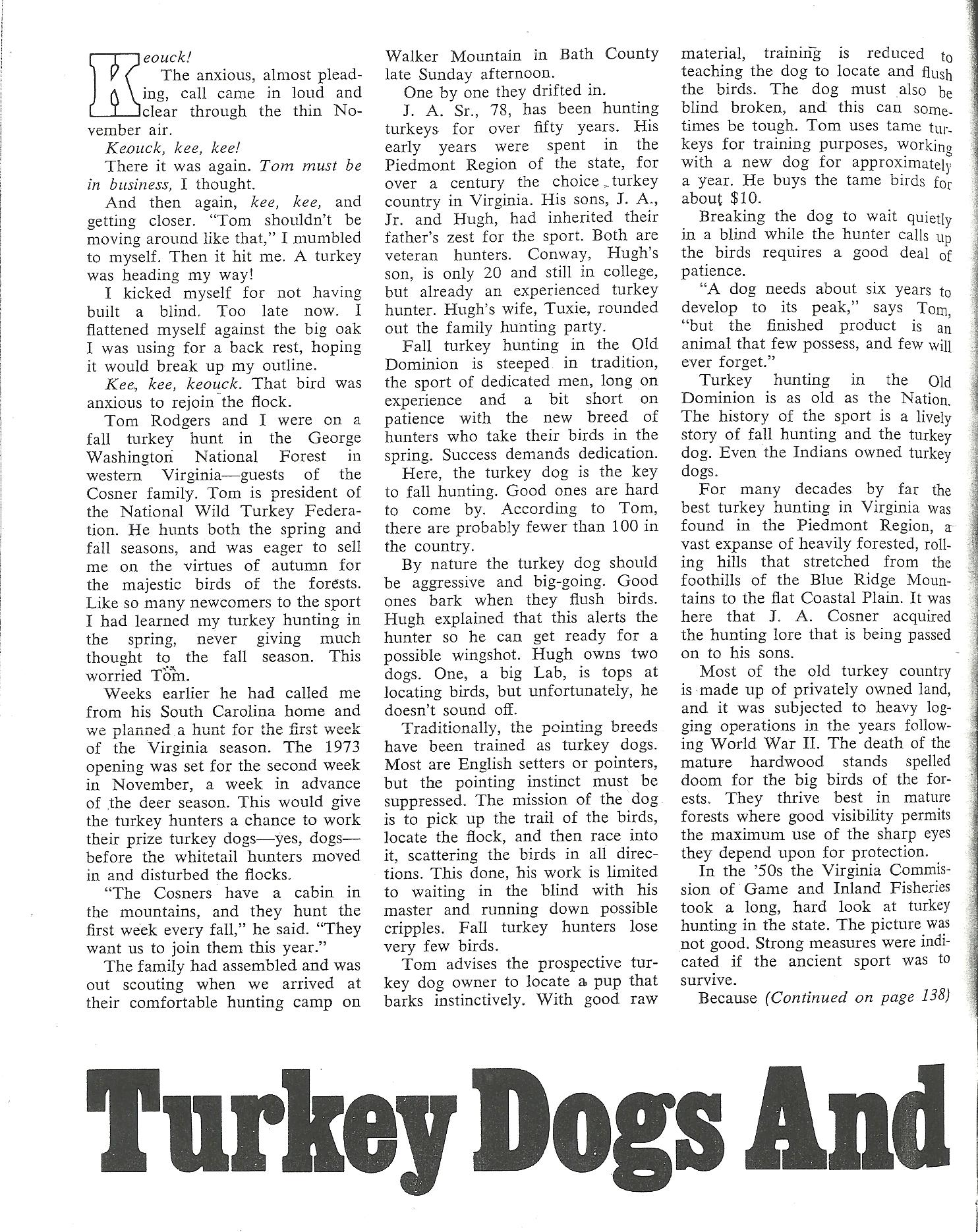

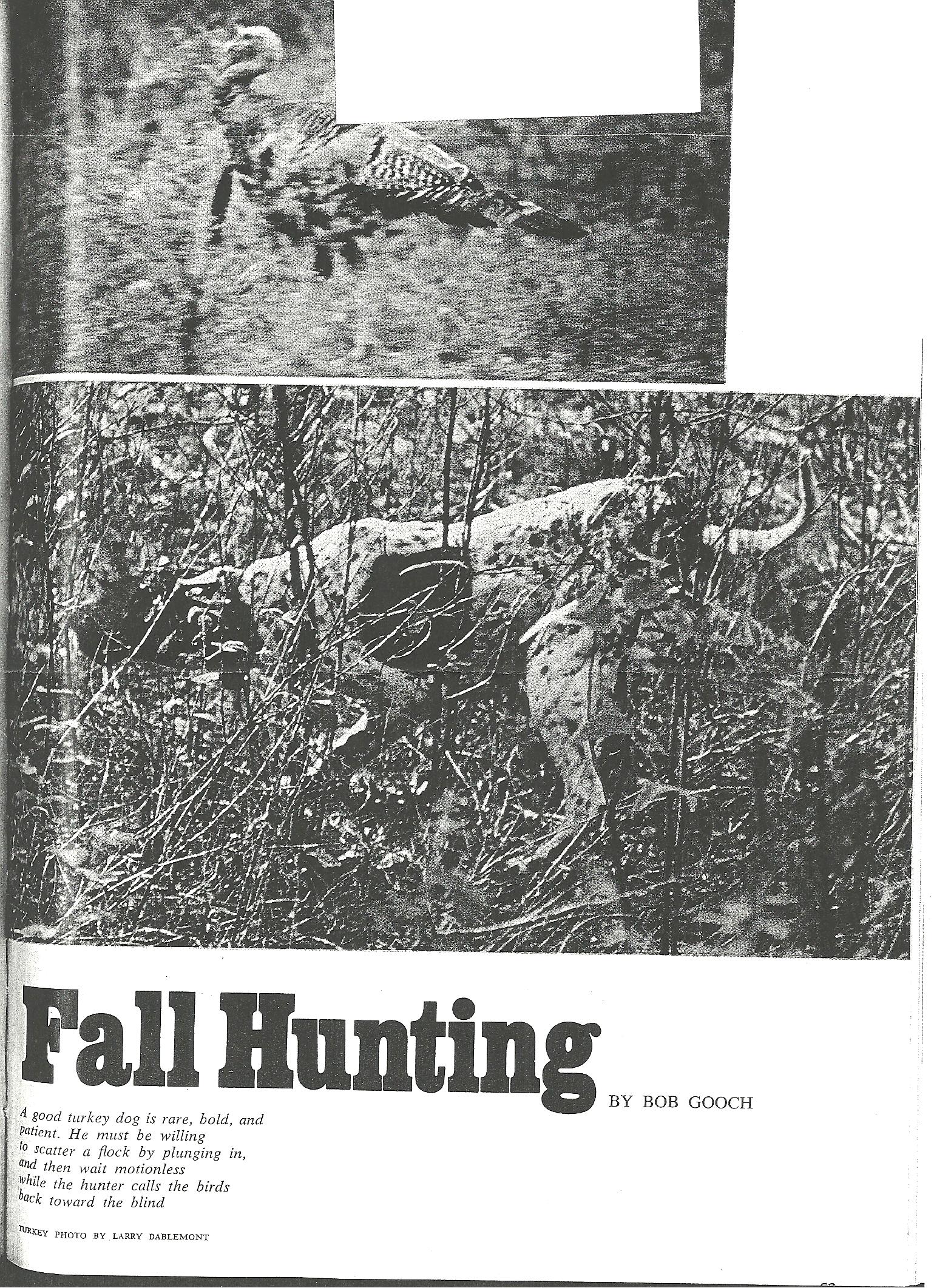

mentioned on this site, unless noted otherwise:1607 English hunters in Jamestown, Virginia continued the European tradition of hunting wild game with trained canines and learned from the local Indian tribes. 1608 "At Jamestown in 1608, the only domestic animals kept by the Indians were curs such as the keepers have in England. They were used for hunting turkey and other game." The Wild Turkey - Its History and Domestication; A.W. Schorger, Univ. of OK Press. 1724 M. Le Page Du Pratz, The History of Louisiana. 1840 Audubon- Arthur Cleveland Bent. 1843 to 1845 Captain George A. McCall - Fort Scott, Kansas.  1853 The Boy Hunters by Captain Mayne Reid. 1863 Baily's Magazine Of Sports And Pastimes, Volume 6 1883 Diomed; The Life, Travels, and Observations of a Dog. 1885 Theodore Roosevelt - Hunting Trips of a Ranchman. 1885 Yelping Up Wild Turkeys - Harper's Weekly drawn by W.L. Sheppard. 1866 A Hunter's Experiences in the Southern States of America. 1889 Autobiography of an Octogenarian - Robert Enoch Withers, Roanoke (Hie-a-way... the finest turkey dog I ever saw. VA page) 1891 Camp-fires Of The Everglades, Or, Wild Sports In The South Charles Edward Whitehead 1904 January issue Field & Stream: "A common cur dog - country raised, makes the best turkey dog for use in stalking." 1910 Chas. L. Jordan, quoted in The Wild Turkey and Its Hunting by Edward A. McIlhenny (FAQ page). 1913 Blackfeet and buffalo: memories of life among the Indians by James Willard Schultz "A companion for him was my son's purebred English shepherd Zora, a fine turkey dog ..."  1921

Hunter

- Trader Trapper Volume 43 (Museum

page). 1921

Hunter

- Trader Trapper Volume 43 (Museum

page).1926: Imaginations, by William Carlos Williams. "You get a turkey dog. He flushes the covey. You then build a blind of brushwood and hide in it, the dog too, since his work is done. Take out the turkey-call and blow it skillfully. The birds will then come creeping in to be killed." 1936 Birds of America by T. Gilbert Pearson. "They are usually hunted with dogs. A well- trained Turkey dog upon finding a group of birds rushes barking among them, thus causing the Turkeys to fly in all directions. The hunter goes to the spot, erects a small blind of logs or brush ... 1943 The Wild Turkey in Virginia by Mosby and Handley (History page). 1973 November 2, Tom Rodgers (click here to read it on Google, or read the jpegs below) - founder of the National Wild Turkey Federation (NWTF), was hunting with friends (from Spotsylvania), near the WV line, when Tom said there are probably fewer than 100 turkey dogs in the country. The article mentions Kit Shaffer and says when they introduced spring hunting in Virginia, the Commission reasoned they would be killing old gobblers too sterile to be reproductive, but too egotistical to let the younger toms near the hens (and it also says the Indians had turkey dogs.). As the trap and transplant restoration became successful, hunting turkeys in the spring (like the Indians did), became more popular. Thanks to the Virginians and Pennsylvanians (and surrounding states), the fall hunting with a dog tradition was kept alive. If your ancestors hunted fall turkey with trained dogs, tell us about it, before their history is lost forever. The first sheet below includes the statement: "Even the Indians owned turkey dogs." See page 1, last column.       |

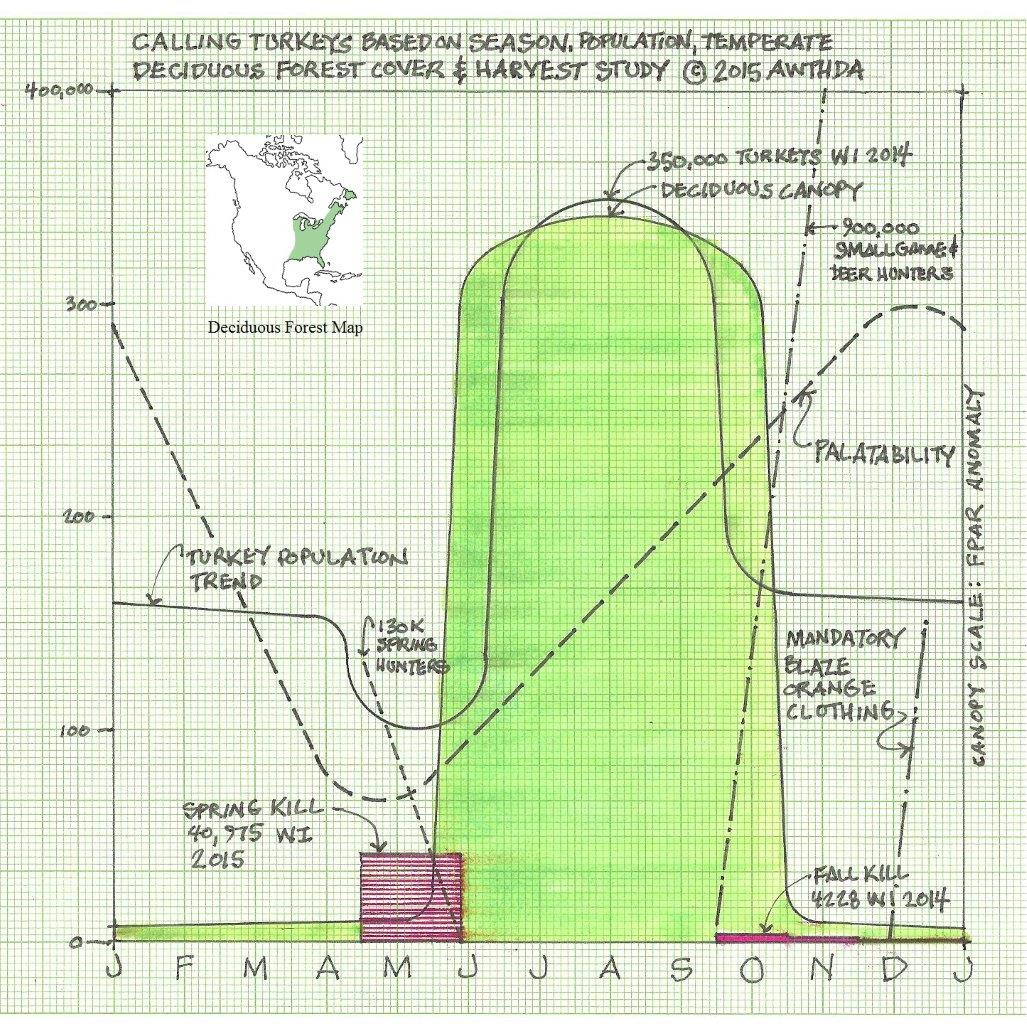

This graph

illustrates the difficulty of calling turkeys in the fall

and winter, taking into account the leafy cover of the

hardwood forest, the seasons, the amount of hunting

pressure, how much the turkeys have been pushed around by

hunters pursuing other game, the palatibility of the meat,

total kill and blaze orange clothing requirements, using

Wisconsin as a base, throughout the calendar year. This graph

illustrates the difficulty of calling turkeys in the fall

and winter, taking into account the leafy cover of the

hardwood forest, the seasons, the amount of hunting

pressure, how much the turkeys have been pushed around by

hunters pursuing other game, the palatibility of the meat,

total kill and blaze orange clothing requirements, using

Wisconsin as a base, throughout the calendar year.I didn't include the conifer cover, because that would be a straight line across, according to what percentage of evergreens make up the local forestland. Where I live in WI, ~15% of the forest consists of evergreens. When the leaves go off the hardwoods about October 15th, the majority of scattered turkeys will fly into the conifers. By November they're reluctant to be called out of their snug sanctuary and by December it's impossible to seduce a turkey to leave their secure abode, especially after being flushed by a dog. When there's snow on the ground, there's no way a black bird is going to leave an evergreen tree to be a target in the snow (maybe in 3 or 4 hours of calling, if you can endure the cold). I considered including a temperature and precipitation line, but that is what it is - we'll hunt anyway, if we can. In September, the young birds are naive, the adult birds have had a relaxing summer and they're all eager to regroup and receptive to calling. By October, the turkeys have been pushed around more by the small game and archery hunters in the woods. In September and October, while the dog might efficiently scatter a small flock, there can be more flocks adjacent to the original that we weren't aware of, until we sat down and called for an hour, only to have them fly down to a flock just out of sight and hearing. Either we need to let the dog run longer, to find adjacent birds, or bring in more dogs and hunters from other sides of the woods, to try and get every single bird off the ground. Then our success rate of calling birds goes up, earlier in the season. As the temperature gets colder, the small flocks become big flocks. Where there used to be 5 or 6 small flocks, there's now one big flock and they're hard to find. The big flocks really need more than one dog to properly scatter them, or calling is futile. Tell me what you think. |

Among

all

the Tribes of Canada, there is not one that lives in so

great abundance of everything as do the Illinois. Their

rivers are covered with swans bustards, ducks, and teal.

We can hardly travel a league without meeting a prodigious

multitude of Turkeys, which go in troops, sometimes to the

number of 200, They are larger than those that are seen in

France. I had the curiosity to weigh one of them, and it

weighed thirty-six livres. They have a sort of hairy beard

at the neck, which is half a foot long. Among

all

the Tribes of Canada, there is not one that lives in so

great abundance of everything as do the Illinois. Their

rivers are covered with swans bustards, ducks, and teal.

We can hardly travel a league without meeting a prodigious

multitude of Turkeys, which go in troops, sometimes to the

number of 200, They are larger than those that are seen in

France. I had the curiosity to weigh one of them, and it

weighed thirty-six livres. They have a sort of hairy beard

at the neck, which is half a foot long.Travels and Explorations of the Jesuit Missionaries in New France 1610 - 1791 |

KEEPING LONGHAIRED

DOGS FREE OF BURDOCKS AND STICK-TITES: KEEPING LONGHAIRED

DOGS FREE OF BURDOCKS AND STICK-TITES: A Setter is good-looking 365 days of the year. If her beautiful hair requires a little more work on 20 or 30 days of hunting when the burs and stick-tites are bad, it's a small price to pay. For years I used Avon Skin so Soft, it works as a mosquito repellent also, but when the burdock and stick-tites are the worst, Skin so Soft isn't very effective. Since October 2013 I used Straight Arrow's UPDATE December 2018 - Even better yet is Cowboy Magic Concentrated Detangler & Shine 32 Ounce |

Why canines

can't find turkey nests in the spring: Why canines

can't find turkey nests in the spring:Wisconsin Outdoor News - July 1, 2011 How do ground-nesting gamebirds pull off a hatch? By Bob Zink, Contributing Writer This is not the favorite time of year for my English setter and my Drahthaar. Every day they check me out in the morning when I come down the stairs to see if, by any chance, I m wearing hunting clothes. After this wardrobe check, they begin their ritualistic dances that precede a morning treat. Gotta love their ability to switch to Plan B and still be your best friend. But I got to thinking about what they'd do if they were afield now (which I think is illegal). I'm confident that they don't miss many birds when they re hunting. A few molecules of scent from a bird that passes their noses gets their attention, and anything more than a few gets a solid point. So, they could find just about any hen sitting on a nest, be it a ruffed grouse, a sharp-tailed grouse, a Hungarian partridge, a woodcock, or a pheasant. After all the hen sits for considerable periods and this has to lead to a good downwind scent cone that my dogs would catch. They might miss a rapidly moving bird (like a running pheasant), but not a sitting hen. That is why you are not supposed to be out running your dogs during the bird nesting season. Even if they don t catch a bird, they can disturb it. When undisturbed, most incubating hens leave their nests quietly, skulking away to avoid detection. But a sudden flush could well be an issue if a predator notices and later finds the nest, or the hen doesn t have the opportunity to cover the eggs (to conceal and keep them warm).  Or am I over-estimating my

dogs ability? It is folklore in some places that hunting

dogs cannot find a quail or woodcock hen sitting on a

nest? Maybe they just weren t well trained. But, what

about coyotes, fox, and wolves that depend on their noses

for food? Surely they have even better scenting ability

than a hunting dog? If so, how could a hen on a nest ever

be successful during the three-week incubation period?

Wouldn t a coyote or fox cross a scent cone coming from

the sitting hen at least once? Or am I over-estimating my

dogs ability? It is folklore in some places that hunting

dogs cannot find a quail or woodcock hen sitting on a

nest? Maybe they just weren t well trained. But, what

about coyotes, fox, and wolves that depend on their noses

for food? Surely they have even better scenting ability

than a hunting dog? If so, how could a hen on a nest ever

be successful during the three-week incubation period?

Wouldn t a coyote or fox cross a scent cone coming from

the sitting hen at least once?A bit about the scent cone, which we should know from our dogs. A predator is more likely to encounter a scent cone when it is long and linear. This occurs when airflow is smooth and not turbulent. If air is turbulent and of high velocity, the scent cone is hard to locate, as the scent molecules are dispersed and don t form a direct line back to the nest. Also, a scent cone can be lifted over a predator s nose by updrafts. Now, if these theoretical ideas are correct, birds can hide from olfactory predators by putting their nests where updrafts, turbulence, and faster winds predominate. Another key to hiding from olfactory predators comes from wax or oil. All birds have a gland (one of the few skin glands birds have) located on top of their tail at its base. The gland goes by various names, including preen gland or uropygial gland. It produces an oil that birds get by squeezing the gland with their beaks, getting the oil onto their bills, and then preening their feathers. To get it on their heads, they can use their feet. For a long time we have recognized that these oily or waxy secretions are how birds waterproof their feathers. These oils allow ducks to float. They allow a bird to fly through a rainstorm. Without the oils the feathers are not waterproof and the birds become water logged. A duck would drown, and a robin would likely perish flying through the rain. The reason is that without waterproofing the bird becomes thoroughly wet, and if it s at all cold, the bird dies. If it s not cold, it won t be able to fly, making it vulnerable until its feathers dry out. Keeping the feathers waterproofed is a life-and-death deal.  But

there

is a cost to this method of waterproofing, namely that

predators can smell. Remember, what you smell are

particles in the air. The chemical composition of these

oils has been studied. Two basic types are known, for

simplicity, monoesters and diesters, which differ in their

characteristics. Diesters are heavier and, therefore, less

volatile than monoesters, so diesters would make a scent

cone harder to detect because the scent cone would sink.

Why two types of preen oils? It is known that some birds

switch from monoesters to diesters during the breeding

season. Could this have a nest-concealing function? But

there

is a cost to this method of waterproofing, namely that

predators can smell. Remember, what you smell are

particles in the air. The chemical composition of these

oils has been studied. Two basic types are known, for

simplicity, monoesters and diesters, which differ in their

characteristics. Diesters are heavier and, therefore, less

volatile than monoesters, so diesters would make a scent

cone harder to detect because the scent cone would sink.

Why two types of preen oils? It is known that some birds

switch from monoesters to diesters during the breeding

season. Could this have a nest-concealing function?Researchers in the Netherlands did some experiments, using a trained 6-year-old German shepard. They trained the dog to find tubes that contained monoesters or diesters (versus blanks), and in hundreds of trials, the dog did not make a single mistake. They then tested monesters versus diesters, and the dog had much more trouble finding diesters, especially at lower concentrations. So, if you re a nesting hen, this chemical switch to diesters also functions as an olfactory camouflage. The results from the Dutch researchers suggest that a switch to a diester preen oil might explain why hunting dogs struggle to find woodcock or quail hens on their nests. Of course, then you would ask why don t they use diester oils year-around? They might be more costly to produce, or be less efficient as waterproofing. They might affect the way the feathers reflect light, and hence change the visual appearance of the bird to other birds. And when not in the breeding season with a nest to protect, simply flying away will suffice even if you re detected by a scent-sniffing predator, so you want the best preen oil possible in the non-nesting season even if it is easier to smell. There have been some other hints that birds behave in ways to mediate the scents they produce. For example, a study of sharp-tailed grouse showed that when they are loafing, they stood in places with greater updrafts, wind velocities, and atmospheric turbulence making them harder to detect by scent-seeking canids. In a study of greater sage-grouse, researchers determined that nests were located in a way that inhibited both visual and olfactory predators. Raptors and ravens will eat eggs and young, and concealing the nest from them also is important. In many sage-grouse nesting areas, there are both visual and olfactory predators, so the birds balance the threats by putting nests in places that are equally difficult for the two types of predators, thereby splitting the difference. The camouflage plumage of nesting hens also helps avoid predators. The preen gland secretions are fascinating. Evolved as a way to waterproof plumage, birds incurred a cost by giving away their locations to olfactory predators. To mitigate this, natural selection favored a switch to a less detectable but still functional oil (diester) in the nesting season, to provide its own scent-elimination system. (And here we thought that we thought of this first). This then seems to be a primary way that ground nesting grouse avoid losing their nests to predators like coyotes, foxes and wolves. And, other mammalian nest predators have good senses of smell, like skunks, raccoons, weasels, and elk yes, an elk was recorded on video eating sage-grouse eggs. Remember that deer that smelled you last year, even after your scent-eliminating shower, and with your scent-free clothing, hat, boots and gum? It turns out that even our whitetails will eat eggs and young if they find a nest. This is why the probability of a successful nest is rather low, and there is intense natural selection on nesting hens to avoid detection. Of course, nature is never static. If you re a predator thwarted by birds chemical switch to diesters while on the nest, the onus is on you to be better at detecting them. The more we learn, the more we realize that nature is an ever-evolving arms race between predator and prey. Darwin would have loved it. Compliments of Dean Bortz - Editor, Wisconsin Outdoor News The entire studies Bob Zink refers to, in original format: full text click here or here. Preening or Uropygial Gland in Birds - A Bird's Oil Gland - also known as Uropygial Gland or Preen Gland - Location & Function: |

| That age old question, should

you get a male or a female puppy to hunt turkeys with?

While male dogs are bigger and stronger, with more endurance, they're distracted by females year round. In contrast, females only seek males for a week, twice a year. That's one reason females are considered more focused and easier to train. Nevertheless, I repeat my counsel: a bitch is more faithful than a dog, the intricacies of her mind are finer, richer and more complex than his, and her intelligence is generally greater of all creatures the one nearest to man in the fineness of its perceptions and in its capacity to render true friendship is a bitch. Man Meets Dog - Konrad Lorenz |

Farmers Know Best: A

friendly old farmer said we were welcome to turkey hunt on

his farm, but to keep our dogs away from the pasture.

Because when his cattle see dogs, the cattle will lose

weight running at the dogs, he's fattening them up for

market and doesn't want them running. Our dogs won't chase

cattle, but I've often seen cattle chasing dogs. I was

always more concerned about the dog. Even if the dog is on

the other side of the fence, if cows see a dog, they'll

run across the field to investigate. That happened to us

that day with that farmers cattle, so we quickly called

the dogs away from the fence, so the cattle would quit

looking and running, before the farmer saw they were

running and get upset. I never thought it was a concern if

cows were chasing dogs, especially anyone concerned about

them not gaining weight, but that day I saw exactly what

he meant. A

friendly old farmer said we were welcome to turkey hunt on

his farm, but to keep our dogs away from the pasture.

Because when his cattle see dogs, the cattle will lose

weight running at the dogs, he's fattening them up for

market and doesn't want them running. Our dogs won't chase

cattle, but I've often seen cattle chasing dogs. I was

always more concerned about the dog. Even if the dog is on

the other side of the fence, if cows see a dog, they'll

run across the field to investigate. That happened to us

that day with that farmers cattle, so we quickly called

the dogs away from the fence, so the cattle would quit

looking and running, before the farmer saw they were

running and get upset. I never thought it was a concern if

cows were chasing dogs, especially anyone concerned about

them not gaining weight, but that day I saw exactly what

he meant. It's something innate in cattle's makeup, even though this was a mix of cows, calves, steers and one bull, they all run at canines, to protect calves, I suppose. The farmer was right, the dogs made the cattle expend unnecessary energy that prevents them from gaining weight. Since then, I keep my dog hidden from livestock whenever possible. I know mules and donkeys will mercilessly drive dogs and coyotes out of a pasture or pen, as will Buffalo, who'll go right through a permanent fence doing it too. That's probably where cattle get it from. To keep the good farmers who let me hunt on their land happy, I'll leash the dogs to keep them away from cattle. Jon. BTW, this picture was taken at a nuclear plant in WI. There's no hunting allowed, so instead they tell everyone to slow down, to stop hitting turkeys. |

| No part of this webpage may be reproduced

in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical,

including photocopy, recording, or any other information

storage or retrieval system without permission in writing

from the AWTHDA. Write to: awthda@turkeydog.org

|

| Home | About

Us |

Books

| Breeds

| Classifieds | FAQ

|

History

| Kit

Shaffer Legislation | Links | Scratchings | Spring | Stories | Tales | Shop in the Store Members are invited to send pictures of yourself and your dog, with a short story like these: Carson Quarles | Earl Sechrist | Frederick Payne 1 | Frederick Payne 2 | Gary Perlstein | Gratten Hepler | Jon Freis 1 | Jon Freis 2 | Larry Case | Marlin Watkins 1 | Marlin Watkins 2 | Mike Joyner | Mike Morrell | Parker Whedon | Randy Carter | Ron Meek 1 | Ron Meek 2 | Tom McMurray | Tommy Barham 1 | Tommy Barham 2 Members Only: Hall of Fame | Members | Museum | Studies | and the States KY | NC | NY | OH | ON | PA | TN | VA | WI | WV © 2011 - 2026 American Wild Turkey Hunting Dog Association All Rights Reserved Permission to copy without written authorization is expressly denied. |